Foreign Interventions By The United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States has been involved in numerous foreign interventions throughout its history. By the broadest definition of military intervention, the US has engaged in nearly 400 military interventions between 1776 and 2019, with half of these operations occurring since 1950 and over 25% occurring in the post-Cold War period. The objectives for these interventions have revolved around economy, territory, social protection, regime change, protection of US citizens and diplomats, policy change, empire, and regime building.

There have been two dominant schools of thought in the United States about foreign policy— interventionism, which encourages military, diplomatic, and economic intervention in foreign countries—and

The 19th century saw the United States transition from an isolationist, post-

The 19th century saw the United States transition from an isolationist, post- * 1898: The short but decisive Spanish–American War saw overwhelming American victories at sea and on land against the Spanish Kingdom. The U.S. Army, relying significantly on volunteers and state militia units, invaded and occupied Spanish-controlled Cuba, subsequently granting it independence. The

* 1898: The short but decisive Spanish–American War saw overwhelming American victories at sea and on land against the Spanish Kingdom. The U.S. Army, relying significantly on volunteers and state militia units, invaded and occupied Spanish-controlled Cuba, subsequently granting it independence. The  ** 1904: When European governments began to use force to pressure Latin American countries to repay their debts, Theodore Roosevelt announced his "

** 1904: When European governments began to use force to pressure Latin American countries to repay their debts, Theodore Roosevelt announced his "

A series of Neutrality Acts passed by the U.S. Congress in the 1930s sought to return foreign policy to non-interventionism in European affairs, as it had been prior to the American entry into World War I. However, Nazi German

A series of Neutrality Acts passed by the U.S. Congress in the 1930s sought to return foreign policy to non-interventionism in European affairs, as it had been prior to the American entry into World War I. However, Nazi German

In 1945, the United States and Soviet Union occupied Korea to disarm the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces that occupied the Korean peninsula. The U.S. and Soviet Union split the country at the 38th parallel and each installed a government, with the Soviet Union installing a Stalinist Kim Il-sung in North Korea and the US supporting anti-communist

In 1945, the United States and Soviet Union occupied Korea to disarm the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces that occupied the Korean peninsula. The U.S. and Soviet Union split the country at the 38th parallel and each installed a government, with the Soviet Union installing a Stalinist Kim Il-sung in North Korea and the US supporting anti-communist  At the end of the Eisenhower administration, a campaign was initiated to deny Cheddi Jagan power in an independent

At the end of the Eisenhower administration, a campaign was initiated to deny Cheddi Jagan power in an independent  In 1975 it was revealed by the

In 1975 it was revealed by the

Months after the

Months after the

In 1990 and 1991, the U.S. intervened in Kuwait after a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, and led a coalition to repel invading Iraqi forces led by Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, in what became known as the Gulf War. On February 26, 1991, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. The U.S., UK, and France responded to popular Shia and Kurdish demands for no-fly zones, and intervened and created no-fly zones in Iraq's south and north to protect the Shia and Kurdish populations from Saddam's regime. The no-fly zones cut off Saddam from the country's Kurdish north, effectively granting autonomy to the Kurds, and would stay active for 12 years until the

In 1990 and 1991, the U.S. intervened in Kuwait after a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, and led a coalition to repel invading Iraqi forces led by Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, in what became known as the Gulf War. On February 26, 1991, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. The U.S., UK, and France responded to popular Shia and Kurdish demands for no-fly zones, and intervened and created no-fly zones in Iraq's south and north to protect the Shia and Kurdish populations from Saddam's regime. The no-fly zones cut off Saddam from the country's Kurdish north, effectively granting autonomy to the Kurds, and would stay active for 12 years until the

After the

After the  In 2003, the U.S. and a multi-national

In 2003, the U.S. and a multi-national  2013–2014 saw the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/ISIS) terror organization in the Middle East. In June 2014, during

2013–2014 saw the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/ISIS) terror organization in the Middle East. In June 2014, during

isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entang ...

, which discourages these.

The 19th century formed the roots of United States foreign interventionism, which at the time was largely driven by economic opportunities in the Pacific and Spanish-held Latin America along with the Monroe Doctrine, which saw the U.S. seek a policy to resist European colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turkish people, Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the mode ...

in the Western hemisphere. The 20th century saw the U.S. intervene in two world wars in which American forces fought alongside their allies in international campaigns against Imperial Japan, Imperial and Nazi Germany, and their respective allies. The aftermath of World War II

The aftermath of World War II was the beginning of a new era started in late 1945 (when World War II ended) for all countries involved, defined by the decline of all colonial empires and simultaneous rise of two superpowers; the Soviet Union (US ...

resulted in a foreign policy of containment aimed at preventing the spread of world communism. The ensuing Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

resulted in the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy

Kennedy may refer to:

People

* John F. Kennedy (1917–1963), 35th president of the United States

* John Kennedy (Louisiana politician), (born 1951), US Senator from Louisiana

* Kennedy (surname), a family name (including a list of persons with t ...

, Carter, and Reagan Doctrines, all of which saw the U.S. embrace espionage, regime change, proxy conflicts

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

, and other clandestine activity internationally against the Soviet Union.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the U.S. emerged as the world's sole superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural s ...

and, with this, continued interventions in Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, the U.S. and its NATO allies launched the Global War on Terror

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is an ongoing international counterterrorism military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks. The main targets of the campaign are militant I ...

in which the U.S. waged international counterterrorism

Counterterrorism (also spelled counter-terrorism), also known as anti-terrorism, incorporates the practices, military tactics, techniques, and strategies that Government, governments, law enforcement, business, and Intelligence agency, intellig ...

campaigns against various extremist groups such as al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

and the Islamic State in various countries. The Bush Doctrine of preemptive war saw the U.S. invade Iraq in 2003 and saw the military expand its presence in Africa and Asia via a revamped policy of foreign internal defense. The Obama administration

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. A Democrat from Illinois, Obama took office following a decisive victory over Republican ...

's 2012 " Pivot to East Asia" strategy sought to refocus U.S. geopolitical efforts from counter-insurgencies in the Middle East to increasing American involvement in East Asia, as part of a policy to contain an ascendant China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

The United States Navy has been involved in anti- piracy activity in foreign territory throughout its history, from the Barbary Wars to combating modern piracy off the coast of Somalia

Piracy off the coast of Somalia occurs in the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel and Somali Sea, in Somali territorial waters and other surrounding areas and has a long and troubled history with different perspectives from different communities. I ...

and other regions.

Post-colonial

The 19th century saw the United States transition from an isolationist, post-

The 19th century saw the United States transition from an isolationist, post-colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 a ...

regional power to a Trans-Atlantic and Trans-Pacific power.

The first and second Barbary Wars of the early 19th century were the first nominal foreign wars waged by the United States following independence. Directed against the Barbary States of North Africa, the Barbary Wars were fought to end piracy against American-flagged ships in the Mediterranean Sea, similar to the Quasi-War with the French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

.

The founding of Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

was privately sponsored by American groups, primarily the American Colonization Society, but the country enjoyed the support and unofficial cooperation of the United States government.

Notable 19th century interventions included:

* Repeated U.S. interventions in Chile, starting in 1811, the year after its independence from the Spanish Empire.

* 1846 to 1848: During the Mexican–American War, Mexico and the United States warred over Texas, California and what today is the American Southwest but was then part of Mexico. During this war, U.S. Armed Forces troops invaded and occupied parts of Mexico, including Veracruz and Mexico City.

* 1854: Commodore Matthew Perry negotiated the Convention of Kanagawa, which effectively ended Japan's centuries of national isolation, opening the country to Western trade and diplomacy. The U.S. later advanced the Open Door Policy in 1899 that guaranteed equal economic access to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and support of Chinese territorial and administrative integrity.

* 1871: The U.S. dispatched an expeditionary force to Korea after failed attempts to ascertain the fate of the armed merchant ship ''General Sherman'', which was attacked during an unsuccessful attempt to open up trade with the isolationist kingdom in 1866. After being ambushed, the 650-man American expeditionary force launched a punitive campaign, capturing and occupying several Korean forts and killing over 200 Korean troops.

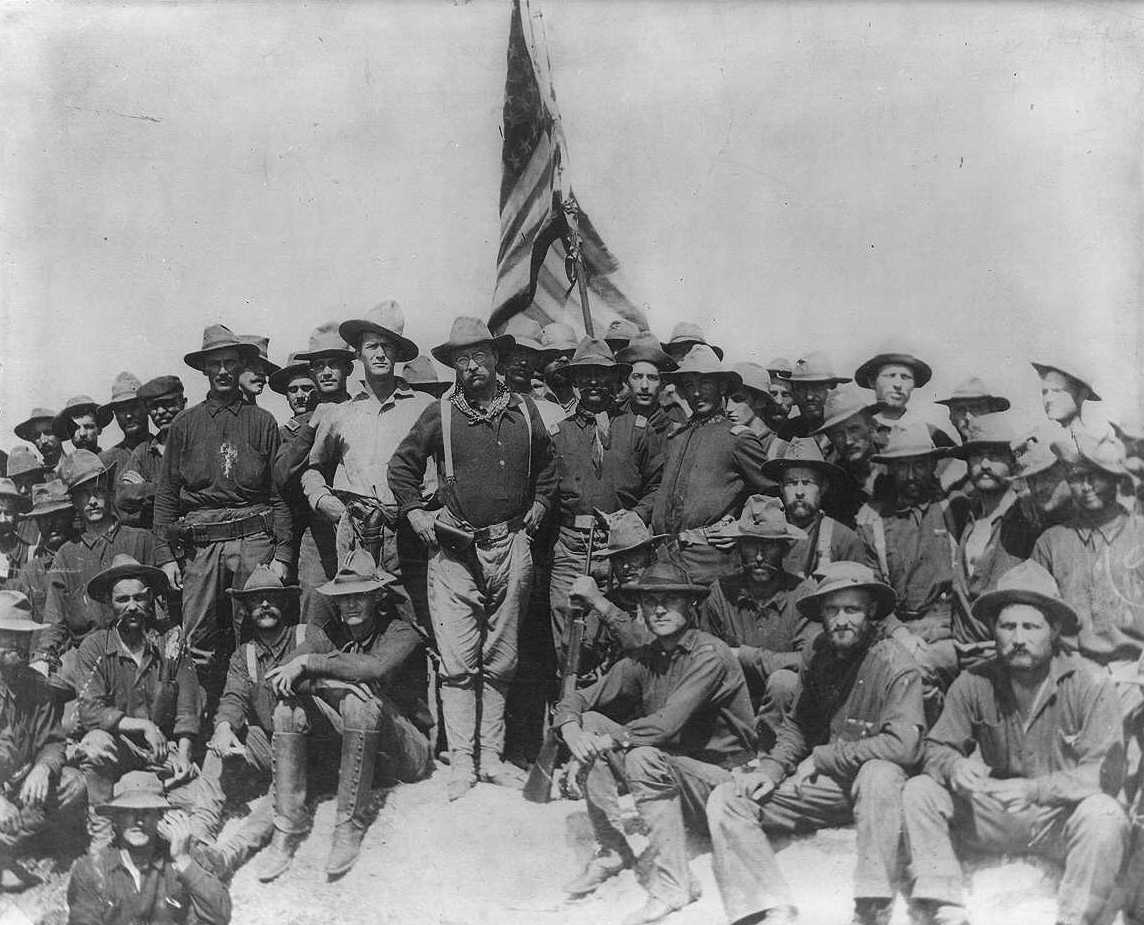

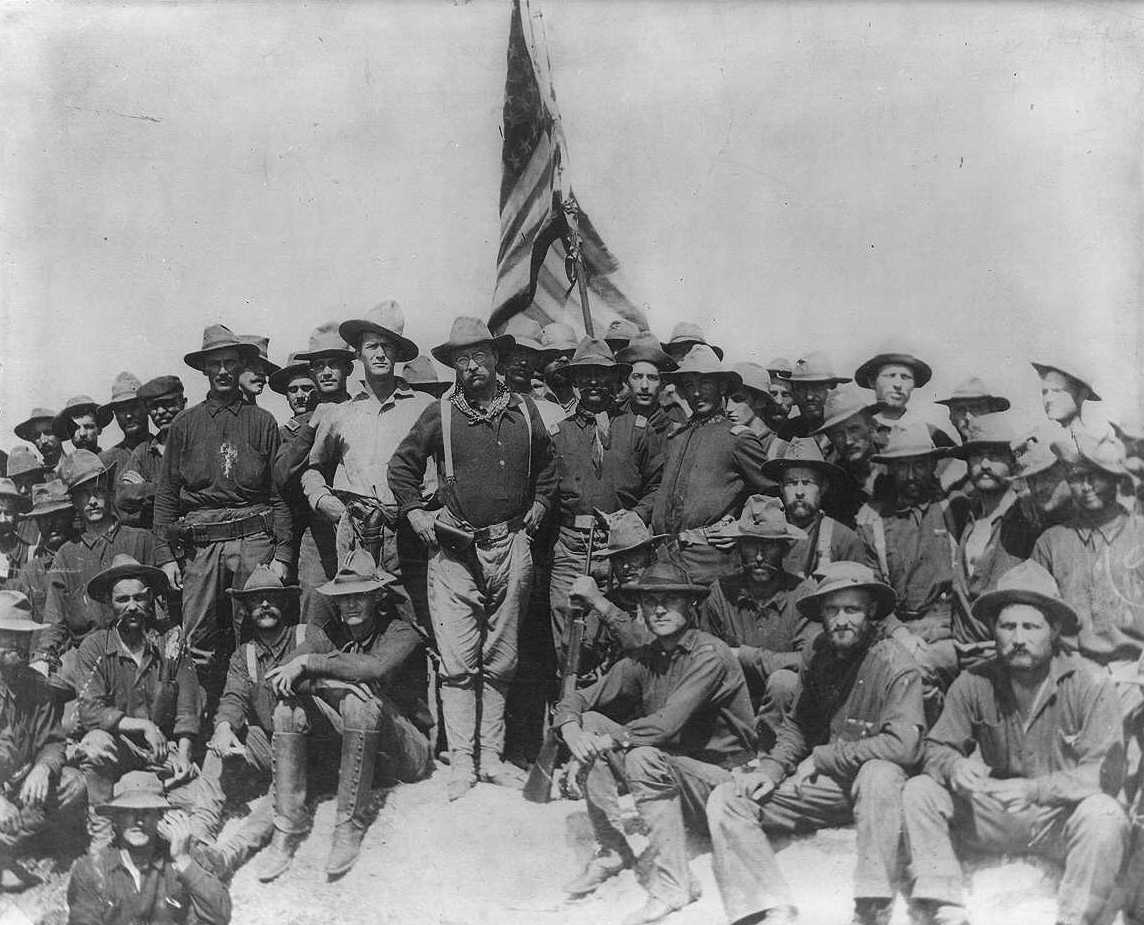

* 1898: The short but decisive Spanish–American War saw overwhelming American victories at sea and on land against the Spanish Kingdom. The U.S. Army, relying significantly on volunteers and state militia units, invaded and occupied Spanish-controlled Cuba, subsequently granting it independence. The

* 1898: The short but decisive Spanish–American War saw overwhelming American victories at sea and on land against the Spanish Kingdom. The U.S. Army, relying significantly on volunteers and state militia units, invaded and occupied Spanish-controlled Cuba, subsequently granting it independence. The peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surr ...

saw Spain cede control over its colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States. The U.S. Navy set up coaling stations there and in Hawaii. See also: Bath Iron Works

The early decades of the 20th century saw a number of interventions in Latin America by the U.S. government often justified under the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. President William Howard Taft viewed Dollar diplomacy as a way for American corporations to benefit while assisting in the national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military atta ...

goal of preventing European powers from filling any possible financial power vacuum.

* 1898 to 1935: The United States launched multiple minor interventions into Latin America, resulting in U.S. military presence in Cuba, Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

, Panama (via the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty and Isthmian Canal Commission), Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

(1915–1935), the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) and Nicaragua (1912–1925) & (1926–1933). The U.S. Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through comb ...

began to specialize in long-term military occupation of these countries, primarily to safeguard customs revenues which were the cause of local civil wars.

** 1901: The Platt Amendment amended a treaty between the U.S. and the Republic of Cuba after the Spanish–American War, virtually making Cuba a U.S. protectorate. The amendment outlined conditions for the U.S. to intervene in Cuban affairs and permitted the United States to lease or buy lands for the purpose of the establishing naval bases, including Guantánamo Bay

Guantánamo Bay ( es, Bahía de Guantánamo) is a bay in Guantánamo Province at the southeastern end of Cuba. It is the largest harbor on the south side of the island and it is surrounded by steep hills which create an enclave that is cut off ...

.

** 1904: When European governments began to use force to pressure Latin American countries to repay their debts, Theodore Roosevelt announced his "

** 1904: When European governments began to use force to pressure Latin American countries to repay their debts, Theodore Roosevelt announced his "Corollary

In mathematics and logic, a corollary ( , ) is a theorem of less importance which can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement. A corollary could, for instance, be a proposition which is incidentally proved while proving another ...

" to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the United States would not just prevent but militarily intervene in affairs between European and Latin American governments if European pressure resulted in the Latin countries becoming chronically unstable failed states.

** 1906 to 1909: The U.S. governed Cuba under Governor Charles Magoon.

** 1914: During a revolution in the Dominican Republic, the U.S. navy fired at revolutionaries who were bombarding Puerto Plata, in order to stop the action.

** 1916 to 1924: U.S. Marines occupied the Dominican Republic following 28 revolutions in 50 years. The Marines ruled the nation completely except for lawless parts of the city of Santo Domingo, where warlords still held sway.

* 1899 to 1901: The U.S. organized the China Relief Expedition

The China Relief Expedition was an expedition in China undertaken by the United States Armed Forces to rescue United States citizens, European nationals, and other foreign nationals during the latter years of the Boxer Rebellion, which lasted f ...

during the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

, which saw an eight-nation alliance put down a rebellion by the Boxer secret society and toppled the Qing dynasty's Imperial Army.

* 1899 to 1913: The Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War or Filipino–American War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

saw Filipino revolutionaries revolt against American rule following the Spanish-American War. The U.S. Army deployed 100,000 (mostly National Guard) troops under General Elwell Otis to the Philippines, resulting in the poorly armed and poorly trained rebels to break off into armed bands. The insurgency collapsed in March 1901 when the leader, Emilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who is the youngest president of the Philippines (1899–1901) and is recognized as the first president of the Philippine ...

, was captured by General Frederick Funston and his Macabebe allies. The concurrent Moro Rebellion

The Moro Rebellion (1899–1913) was an armed conflict between the Moro people and the United States military during the Philippine–American War.

The word "Moro" – the Spanish word for "Moor" – is a term for Muslim people who li ...

resulted in the subsequent annexation of the Philippines by the United States.

* 1910 to 1919: The Border War Border War may refer to:

Military conflicts

*Border War or Bleeding Kansas (1854–1859), a series of violent events involving Free-Staters and pro-slavery elements prior to the American Civil War

*Border War (1910–1919), border conflicts betwee ...

along the U.S.-Mexico border saw U.S. forces occupy Veracruz for six months in 1914. U.S. troops intervened in northern Mexico during the Pancho Villa Expedition.

* 1917 to 1920: The U.S. intervened in Europe during World War I. Over the next 18 months, the U.S. would suffer casualties of 116,708 killed and 204,002 wounded. U.S. troops also intervened in the Russian Civil War against the Red Army via the Siberian intervention and the Polar Bear Expedition's North Russia intervention.

World War II

A series of Neutrality Acts passed by the U.S. Congress in the 1930s sought to return foreign policy to non-interventionism in European affairs, as it had been prior to the American entry into World War I. However, Nazi German

A series of Neutrality Acts passed by the U.S. Congress in the 1930s sought to return foreign policy to non-interventionism in European affairs, as it had been prior to the American entry into World War I. However, Nazi German submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

attacks on American vessels in 1941 saw many provisions of the Neutrality Acts largely revoked. The Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940 would ultimately increase the size of the United States Navy by 70%. The British-American destroyers-for-bases deal in September 1940 saw the U.S. transfer 50 Navy destroyers to the Royal Navy in exchange for rent-free, 99-year leases over various British imperial possessions. The U.S. gained the rights to establish new military bases in Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

, British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was S ...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, the Bahamas, the southern coast of Jamaica, the western coast of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

, the Gulf of Paria, the Great Sound

The Great Sound is large ocean inlet (a sound) located in Bermuda. It may be the submerged remains of a Pre- Holocene volcanic caldera. Other geologists dispute the origin of the Bermuda Pedestal as a volcanic hotspot.

Geography

The Great So ...

and Castle Harbour Castle Harbour is a large natural harbour in Bermuda. It is located between the northeastern end of the main island and St. David's Island. Originally called ''Southampton Port'', it was renamed as a result of its heavy fortification in the early ...

, Bermuda.

During the Second World War, the United States deployed troops to fight in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific. The U.S. was a key participant in many battles, including the Battle of Midway, the Normandy landings, and the Battle of the Bulge. In the time period between December 7, 1941 to September 2, 1945, more than 400,000 Americans were killed in the conflict. After the war, American and Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

troops occupied both Germany and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

. The U.S. maintains garrisoned military forces in both Germany and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

today.

The United States also gave economic support to a large number of countries and movements who were opposed to the Axis powers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's cash and carry policy was a precursor to what would become the Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

program, which "lent" a wide array of resources and weapons to many countries, especially Great Britain and the USSR, ostensibly to be repaid after the war. In practice, the United States frequently either did not push for repayment or "sold" the goods for a nominal price, such as 10% of their value. Significant aid was also sent to France and Taiwan, and resistance

Resistance may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Comics

* Either of two similarly named but otherwise unrelated comic book series, both published by Wildstorm:

** ''Resistance'' (comics), based on the video game of the same title

** ''T ...

movements in countries occupied by the Axis.

Cold War

Following the Second World War, the U.S. helped form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949 to resist communist expansion and supported resistance movements and dissidents in the communist regimes of Central and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union during a period known as theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. One example is the counterespionage operations following the discovery of the Farewell Dossier which some argue contributed to the fall of the Soviet regime. After Joseph Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade, the United States, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several other countries began the massive " Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with up to 4,700 tons of daily necessities.Nash, Gary B. "The Next Steps: The Marshall Plan, NATO, and NSC-68." The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society. New York: Pearson Longman, 2008. P 828. U.S. Air Force pilot Gail Halvorsen created "Operation Vittles

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road ...

", which supplied candy to German children. In May 1949, Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade. The U.S. spent billions to rebuild Europe and aid global development through programs such as the Marshall Plan.

In 1945, the United States and Soviet Union occupied Korea to disarm the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces that occupied the Korean peninsula. The U.S. and Soviet Union split the country at the 38th parallel and each installed a government, with the Soviet Union installing a Stalinist Kim Il-sung in North Korea and the US supporting anti-communist

In 1945, the United States and Soviet Union occupied Korea to disarm the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces that occupied the Korean peninsula. The U.S. and Soviet Union split the country at the 38th parallel and each installed a government, with the Soviet Union installing a Stalinist Kim Il-sung in North Korea and the US supporting anti-communist Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee (, ; 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965) was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960.

Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Ko ...

in South Korea, whom was elected president in 1948. Both leaders were authoritarian dictators. Tensions between the North and South erupted into full-scale war in 1950 when North Korean forces invaded the South. From 1950 to 1953, U.S. and United Nations forces fought communist Chinese and North Korean troops in the Korean War. The war resulted in 36,574 American deaths and 2–3 million Korean deaths. The war ended in a stalemate with the Korean peninsula devastated and every major city in ruins. North Korea was among the most heavily bombed countries in history. Fighting ended on 27 July 1953 when the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed. The agreement created the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) to separate North and South Korea, and allowed the return of prisoners. However, no peace treaty was ever signed, and the two Koreas are technically still at war. U.S. troops have remained in South Korea to deter further conflict.

Throughout the Cold War, the U.S. frequently used the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for covert and clandestine operations against governments and groups considered unfriendly to U.S. interests, especially in the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa. In 1949, during the Truman administration, a coup d'état overthrew an elected parliamentary government in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, which had delayed approving an oil pipeline requested by U.S. international business interests in that region. The exact role of the CIA in the coup is controversial, but it is clear that U.S. governmental officials, including at least one CIA officer, communicated with Husni al-Za'im, the coup's organizer, prior to the March 30 coup, and were at least aware that it was being planned. Six weeks later, on May 16, Za'im approved the pipeline.

In the early 1950s, the CIA spearheaded Project FF

Project FF or Fat Fucker was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) project aimed at pressuring King Farouk of Egypt to make political reforms that would lessen the likelihood of violent political change in the country contrary to American interests ...

, a clandestine effort to pressure Egyptian king Farouk I into embracing pro-American political reforms. After he resisted, the project shifted towards deposing him, and Farouk was subsequently overthrown in a military coup in 1952. In 1953, under U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, the CIA helped Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 October ...

of Iran remove

Remove, removed or remover may refer to:

* Needle remover

* Polish remover

* Staple remover

* Remove (education)

* The degree of cousinship, i.e. "once removed" or "twice removed" - see Cousin chart

See also

* Deletion (disambiguation)

* Moving ( ...

the democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadegh. Supporters of U.S. policy claimed that Mossadegh had ended democracy through a rigged referendum.

In 1952, the CIA launched Operation PBFortune and, in 1954, Operation PBSuccess to depose the democratically elected Guatemalan President

Guatemalan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Guatemala

* A person from Guatemala, or of Guatemalan descent. For information about the Guatemalan people, see Demographics of Guatemala and Culture of Guatemala. For spec ...

Jacobo Árbenz and ended the Guatemalan Revolution. The coup installed the military dictatorship of Carlos Castillo Armas

Carlos Castillo Armas (; 4 November 191426 July 1957) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who was the 28th president of Guatemala, serving from 1954 to 1957 after taking power in a coup d'état. A member of the right-wing Nation ...

, the first in a series of U.S.-backed dictators who ruled Guatemala. Guatemala subsequently plunged into a civil war that cost thousands of lives and ended all democratic expression for decades.

The CIA armed an indigenous insurgency in order to oppose the invasion and subsequent control of Tibet by China and sponsored a failed revolt against Indonesian President Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

in 1958. As part of the Eisenhower Doctrine, the U.S. also deployed troops to Lebanon in Operation Blue Bat. President Eisenhower also imposed embargoes on Cuba in 1958.

Covert operations continued under President John F. Kennedy and his successors. In 1961, the CIA attempted to depose Cuban president Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

through the Bay of Pigs Invasion, however the invasion was doomed to fail when President Kennedy withdrew overt U.S. air support at the last minute. During Operation Mongoose, the CIA aggressively pursued its efforts to overthrow Castro's regime by conducting various assassination attempts on Castro and facilitating U.S.-sponsored terrorist attacks in Cuba. American efforts to sabotage Cuba's national security played a significant role in the events leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, which saw the U.S. blockade the island during a confrontation with the Soviet Union. The CIA also considered assassinating Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba with poisoned toothpaste (although this plan was aborted).

In 1961, the CIA sponsored the assassination of Rafael Trujillo

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina ( , ; 24 October 189130 May 1961), nicknamed ''El Jefe'' (, "The Chief" or "The Boss"), was a Dominican dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from February 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He ser ...

, former dictator of the Dominican Republic. After a period of instability, U.S. troops intervened the Dominican Republic into the Dominican Civil War (April 1965) to prevent a takeover by supporters of deposed left wing president Juan Bosch who were fighting supporters of General Elías Wessin y Wessin

Elías Wessin y Wessin (July 22, 1924 – April 18, 2009) was a Dominican politician and Dominican Air Force general. Wessin led the military coup which ousted the government of Dominican President Juan Bosch in 1963, replacing it with a triumv ...

. The soldiers were also deployed to evacuate foreign citizens. The U.S. deployed 22,000 soldiers and suffered 44 dead. The OAS also deployed soldiers to the conflict through the Inter-American Peace Force. U.S. soldiers were gradually withdrawn from May onwards. The war officially ended on September 3, 1965. The first postwar elections were held on July 1, 1966, conservative Joaquín Balaguer defeated former president Juan Bosch.

At the end of the Eisenhower administration, a campaign was initiated to deny Cheddi Jagan power in an independent

At the end of the Eisenhower administration, a campaign was initiated to deny Cheddi Jagan power in an independent Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

. This campaign was intensified and became something of an obsession of John F. Kennedy, because he feared a "second Cuba". By the time Kennedy took office, the United Kingdom was ready to decolonize British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was S ...

and did not fear Jagan's political leanings, yet chose to cooperate in the plot for the sake of good relations with the United States. The CIA cooperated with AFL–CIO, most notably in organizing an 80-day general strike in 1963, backing it up with a strike fund estimated to be over $1 million. The Kennedy Administration put pressure on Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

's government to help in its effort, ultimately attaining a promise on July 18, 1963, that Macmillan's government would unseat Jagan. This was achieved through a plan developed by Duncan Sandys whereby Sandys, after feigning impartiality in a Guyanese dispute, would decide in favor of Forbes Burnham and Peter D'Aguiar

Peter Stanislaus D'Aguiar ( 1912 – 30 March 1989) was a Guyanese businessman, conservative politician, and minister of finance from 1964 to 1967.

Business career

In 1934, following the death of his father, D'Aguiar became the managing director ...

, calling for new elections based on proportional representation before independence would be considered, under which Jagan's opposition would have better chances to win. The plan succeeded, and the Burnham-D'Aguiar coalition took power soon after winning the election on December 7, 1964. The Johnson administration later helped Burnham fix the fraudulent election of 1968—the first election after decolonization in 1966. To guarantee Burnham's victory, Johnson also approved a well-timed Food for Peace

In different administrative and organizational forms, the Food for Peace program of the United States has provided food assistance around the world for more than 60 years. Approximately 3 billion people in 150 countries have benefited directly fro ...

loan, announced some weeks before the election so as to influence the election but not to appear to be doing so. U.S.–Guyanese relations cooled in the Nixon administration. Henry Kissinger, in his memoirs, dismissed Guyana as being "invariably on the side of radicals in Third World forums."

From 1965 to 1973, U.S. troops fought at the request of the governments of South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

, Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

, and Cambodia during the Vietnam War against the military of North Vietnam and against Viet Cong, Pathet Lao

The Pathet Lao ( lo, ປະເທດລາວ, translit=Pa thēt Lāo, translation=Lao Nation), officially the Lao People's Liberation Army, was a communist political movement and organization in Laos, formed in the mid-20th century. The gro ...

, and Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

insurgents. President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

escalated U.S. involvement following the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, , was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

It is of historic significance because it gave U.S. p ...

. North Vietnam invaded Laos in 1959, and used 30,000 men to build invasion routes through Laos and Cambodia. North Vietnam sent 10,000 troops to attack the south in 1964, and this figure increased to 100,000 in 1965. By early 1965, 7,559 South Vietnamese hamlets had been destroyed by the Viet Cong. The CIA organized Hmong tribes to fight against the Pathet Lao, and used Air America to "drop 46 million pounds of foodstuffs....transport tens of thousands of troops, conduct a highly successful photoreconnaissance program, and engage in numerous clandestine missions using night-vision glasses and state-of-the-art electronic equipment." After sponsoring a coup against Ngô Đình Diệm

Ngô Đình Diệm ( or ; ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician. He was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955), and then served as the first president of South Vietnam (Republic of ...

, the CIA was asked "to coax a genuine South Vietnamese government into being" by managing development and running the Phoenix Program that killed thousands of insurgents. North Vietnamese forces attempted to overrun Cambodia in 1970, to which the U.S. and South Vietnam responded with a limited incursion. The U.S. bombing of Cambodia, called Operation Menu, proved controversial. Although David Chandler argued that the bombing "had the effect the Americans wanted--it broke the communist encirclement of Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh (; km, ភ្នំពេញ, ) is the capital and most populous city of Cambodia. It has been the national capital since the French protectorate of Cambodia and has grown to become the nation's primate city and its economic, indus ...

," others have claimed it boosted recruitment for the Khmer Rouge. North Vietnam violated the Paris Peace Accords

The Paris Peace Accords, () officially titled the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam (''Hiệp định về chấm dứt chiến tranh, lập lại hòa bình ở Việt Nam''), was a peace treaty signed on January 27, 1 ...

after the US withdrew, and all of Indochina had fallen to communist governments by late 1975.

In 1975 it was revealed by the

In 1975 it was revealed by the Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

that the United States had covertly intervened in Chile from as early as 1962, and that from 1963 to 1973, covert involvement was "extensive and continuous". In 1970, at the request of President Richard Nixon, the CIA planned a "constitutional coup" to prevent the election of Marxist leader Salvador Allende in Chile, while secretly encouraging Chilean Armed Forces generals to act against him. The CIA changed its approach after the murder of Chilean general René Schneider

General René Schneider Chereau (; December 31, 1913 – October 25, 1970) was the commander-in-chief of the Chilean Army at the time of the 1970 Chilean presidential election, when he was assassinated during a botched kidnapping attempt. He ...

,Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders (1975)Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

, pages 246–247 and 250–254. offering aid to democratic protestors and other Chilean dissidents. Allende was accused of supporting armed groups, torturing detainees, conducting illegal arrests, and muzzling the press. However, Peter Kornbluh asserts that the CIA destabilized Chile and helped create the conditions for the 1973 Chilean coup d'état

The 1973 Chilean coup d'état Enciclopedia Virtual > Historia > Historia de Chile > Del gobierno militar a la democracia" on LaTercera.cl. Retrieved 22 September 2006.

In October 1972, Chile suffered the first of many strikes. Among the par ...

, which led to years of dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet.

From 1972 to 1975, the CIA armed Kurdish rebels fighting the Ba'athist government of Iraq. In 1973, Nixon authorized Operation Nickel Grass, an overt strategic airlift to deliver weapons and supplies to Israel during the Yom Kippur War, after the Soviet Union began sending arms to Syria and Egypt. The same year, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

claimed the Gulf of Sidra

The Gulf of Sidra ( ar, خليج السدرة, Khalij as-Sidra, also known as the Gulf of Sirte ( ar, خليج سرت, Khalij Surt, is a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea on the northern coast of Libya, named after the oil port of Sidra or ...

as sovereign territory and closed the bay, prompting the U.S. to conduct freedom of navigation operations in the area, as it saw Libya's claims as internationally illegitimate. The dispute resulted in Libyan-U.S. confrontations, including an incident in 1981 in which two U.S. F-14 Tomcats shot down two Libyan Su-22 Fitters over the gulf. In response to purported Libyan involvement in international terrorism, specifically the 1985 Rome and Vienna airport attacks

The Rome and Vienna airport attacks were two major terrorist attacks carried out on 27 December 1985. Seven Arab terrorists attacked two airports in Rome, Italy, and Vienna, Austria with assault rifles and hand grenades. Nineteen civilians were ...

, the Reagan administration launched Operation Attain Document in early 1986, which saw operations in March 1986 that killed 72 Libyans and destroyed multiple boats and SAM

Sam, SAM or variants may refer to:

Places

* Sam, Benin

* Sam, Boulkiemdé, Burkina Faso

* Sam, Bourzanga, Burkina Faso

* Sam, Kongoussi, Burkina Faso

* Sam, Iran

* Sam, Teton County, Idaho, United States, a populated place

People and fictional ...

sites. In April 1986, the U.S. bombed Libya again, killing over 40 Libyan soldiers and up to 30 civilians. The U.S. shot down two Libyan Air Force MiG-23 fighters 40 miles (64 km) north of Tobruk in 1989.

Months after the

Months after the Saur Revolution

The Saur Revolution or Sowr Revolution ( ps, د ثور انقلاب; prs, إنقلاب ثور), also known as the April Revolution or the April Coup, was staged on 27–28 April 1978 (, ) by the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) ...

brought a communist regime to power in Afghanistan, the U.S. began offering limited financial aid to Afghan dissidents through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence, although the Carter administration

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the 39th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. A Democrat from Georgia, Carter took office after defeating incumbent Republican President ...

rejected Pakistani requests to provide arms. After the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

, the United States sought rapprochement with the Afghan government—a prospect that the USSR found unacceptable due to the weakening Soviet leverage over the regime. The Soviets invaded Afghanistan on December 24, 1979, to depose Hafizullah Amin, and subsequently installed a puppet regime. Disgusted by the collapse of detente, President Jimmy Carter began covertly arming Afghan mujahideen

''Mujahideen'', or ''Mujahidin'' ( ar, مُجَاهِدِين, mujāhidīn), is the plural form of ''mujahid'' ( ar, مجاهد, mujāhid, strugglers or strivers or justice, right conduct, Godly rule, etc. doers of jihād), an Arabic term th ...

in a program called Operation Cyclone.

This program was greatly expanded under President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

as part of the Reagan Doctrine. As part of this doctrine, the CIA also supported the UNITA movement in Angola, the Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

movement in Poland, the Contra revolt in Nicaragua, and the Khmer People's National Liberation Front in Cambodia. U.S. and UN forces later supervised free elections in Cambodia. Under Reagan, the US sent troops to Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War as part of a peace-keeping mission. The U.S. withdrew after 241 servicemen were killed in the Beirut barracks bombing

Early on a Sunday morning, October 23, 1983, two truck bombs struck buildings in Beirut, Lebanon, housing American and French service members of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF), a military peacekeeping operation during the Lebane ...

. In Operation Earnest Will, U.S. warships escorted reflagged Kuwaiti oil tankers to protect them from Iranian attacks during the Iran–Iraq War. The United States Navy launched Operation Praying Mantis in retaliation for the Iranian mining of the Persian Gulf during the war and the subsequent damage to an American warship. The attack helped pressure Iran to agree to a ceasefire with Iraq later that summer, ending the eight-year war. Under Carter and Reagan, the CIA repeatedly intervened to prevent right-wing coups in El Salvador and the U.S. frequently threatened aid suspensions to curtail government atrocities in the Salvadoran Civil War. As a result, the death squads made plans to kill the U.S. Ambassador. In 1983, after an internal power struggle ended with the deposition and murder of revolutionary Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, the U.S. invaded Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

in Operation Urgent Fury

The United States invasion of Grenada began at dawn on 25 October 1983. The United States and a coalition of six Caribbean nations invaded the island nation of Grenada, north of Venezuela. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury by the U.S. military, ...

and held free elections. President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

ordered the invasion of Panama ( Operation Just Cause) in 1989 and deposed dictator Manuel Noriega.

Post-Cold War

In 1990 and 1991, the U.S. intervened in Kuwait after a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, and led a coalition to repel invading Iraqi forces led by Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, in what became known as the Gulf War. On February 26, 1991, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. The U.S., UK, and France responded to popular Shia and Kurdish demands for no-fly zones, and intervened and created no-fly zones in Iraq's south and north to protect the Shia and Kurdish populations from Saddam's regime. The no-fly zones cut off Saddam from the country's Kurdish north, effectively granting autonomy to the Kurds, and would stay active for 12 years until the

In 1990 and 1991, the U.S. intervened in Kuwait after a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, and led a coalition to repel invading Iraqi forces led by Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, in what became known as the Gulf War. On February 26, 1991, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. The U.S., UK, and France responded to popular Shia and Kurdish demands for no-fly zones, and intervened and created no-fly zones in Iraq's south and north to protect the Shia and Kurdish populations from Saddam's regime. The no-fly zones cut off Saddam from the country's Kurdish north, effectively granting autonomy to the Kurds, and would stay active for 12 years until the 2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

.

In the 1990s, the U.S. intervened in Somalia as part of UNOSOM I and UNOSOM II, a United Nations humanitarian relief operation that resulted in saving hundreds of thousands of lives. During the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, two U.S. helicopters were shot down by rocket-propelled grenade

A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) is a shoulder-fired missile weapon that launches rockets equipped with an explosive warhead. Most RPGs can be carried by an individual soldier, and are frequently used as anti-tank weapons. These warheads are a ...

attacks to their tail rotors, trapping soldiers behind enemy lines. This resulted in a brief but bitter street firefight; 18 Americans and more than 300 Somalis were killed.

Under President Bill Clinton, the U.S. participated in Operation Uphold Democracy, a UN mission to reinstate the elected president of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, Jean-Bertrand Aristide

Jean-Bertrand Aristide (born 15 July 1953) is a Haitian former Salesian priest and politician who became Haiti's first democratically elected president. A proponent of liberation theology, Aristide was appointed to a parish in Port-au-Prince in ...

, after a military coup. In 1995, Clinton ordered U.S. and NATO aircraft to attack Bosnian Serb targets to halt attacks on UN safe zones and to pressure them into a peace accord. Clinton deployed U.S. peacekeepers to Bosnia in late 1995, to uphold the subsequent Dayton Agreement.

The CIA was involved in the failed 1996 coup attempt against Saddam Hussein.

In response to the 1998 al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

bombings of U.S. embassies in East Africa that killed a dozen Americans and hundreds of Africans, President Clinton ordered Operation Infinite Reach on August 20, 1998, in which the U.S. Navy launched cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhe ...

s at al-Qaeda training camps A training camp is an organized period in which military personnel or athletes participate in a rigorous and focused schedule of training in order to learn or improve skills. Athletes typically utilise training camps to prepare for upcoming events, ...

in Afghanistan and a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

believed to be producing chemical weapons for the terror group. It was the first publicly acknowledged preemptive strike against a violent non-state actor conducted by the U.S. military.

Also, to stop the ethnic cleansing and genocide of Albanians by nationalist Serbians in the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia's province of Kosovo, Clinton authorized the use of U.S. Armed Forces in a NATO bombing campaign against Yugoslavia in 1999, named Operation Allied Force.

A 2016 study by Carnegie Mellon University

Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) is a private research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. One of its predecessors was established in 1900 by Andrew Carnegie as the Carnegie Technical Schools; it became the Carnegie Institute of Technology ...

professor Dov Levin found that the United States intervened in 81 foreign elections between 1946 and 2000, with the majority of those being through covert, rather than overt, actions. A 2021 review of the existing literature found that foreign interventions since World War II tend overwhelmingly to fail to achieve their purported objectives.

War on terror

After the

After the September 11, 2001 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial ...

, under President George W. Bush, the U.S. and NATO launched the global War on Terror, which began in earnest with an intervention to depose the Taliban government in the Afghan War

War in Afghanistan, Afghan war, or Afghan civil war may refer to:

*Conquest of Afghanistan by Alexander the Great (330 BC – 327 BC)

*Muslim conquests of Afghanistan (637–709)

*Conquest of Afghanistan by the Mongol Empire (13th century), see als ...

, which the U.S. suspected of protecting al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

. In December 2009, President Barack Obama ordered a "surge" in U.S. forces to Afghanistan, deploying an additional 30,000 troops to fight al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

and the Taliban insurgency, before ordering a drawdown in 2011. Afghanistan continued to host U.S. and NATO counter-terror and counterinsurgency operations ( ISAF/Resolute Support

Resolute may refer to:

Geography

* Resolute, Nunavut, Canada, a hamlet

* Resolute Bay, Nunavut

* Resolute Mountain, Alberta, Canada

Military operations

* Operation Resolute, the Australian Defence Force contribution to patrolling Australia's Excl ...

and operations Enduring Freedom/ Freedom's Sentinel) until 2021, when the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan amidst the negotiated American-led withdrawal from the country. Over 2,400 Americans, 18 CIA operatives, and over 1,800 civilian contractors, died in the Afghan War. The war in Afghanistan became the longest war in United States history, lasting 19 years and ten months–the Vietnam War lasted 19 years and five months–and cost the U.S. over $2 trillion.

Though "Operation Enduring Freedom" (OEF) usually refers to the 2001–2014 phase of the war in Afghanistan, the term is also the U.S. military's official name for the War on Terror, and has multiple subordinate operations which see American military forces deployed in regions across the world in the name of combating terrorism, often in collaboration with the host nation's central government via security cooperation and status of forces agreement A status of forces agreement (SOFA) is an agreement between a host country and a foreign nation stationing military forces in that country. SOFAs are often included, along with other types of military agreements, as part of a comprehensive security ...

s:

* Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa (OEF-HOA): U.S. forces deployed in Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

, Mauritius, Rwanda

Rwanda (; rw, u Rwanda ), officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator ...

, Seychelles, Somalia, Tanzania, and Uganda.

** Camp Lemonnier is the only permanent U.S. military base in Africa, established in Djibouti in 2002, and supports OEF-HOA operations.

**The Peace Corps re-established a presence in Comoros

The Comoros,, ' officially the Union of the Comoros,; ar, الاتحاد القمري ' is an independent country made up of three islands in southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. It ...

in 2015, and Kentucky National Guard

The Kentucky National Guard comprises the:

*Kentucky Army National Guard

*Kentucky Air National Guard

See also

* Kentucky Active Militia, the state defense force of Kentucky which replaced the Kentucky National Guard during World War I and World ...

personnel have trained Comoros troops.

**The Trump administration increased drone strikes in Somalia

Drone most commonly refers to:

* Drone (bee), a male bee, from an unfertilized egg

* Unmanned aerial vehicle

* Unmanned surface vehicle, watercraft

* Unmanned underwater vehicle or underwater drone

Drone, drones or The Drones may also refer to:

...

and in 2020 launched Operation Octave Quartz, which saw U.S. troops dispersed from the nation and re-positioned to other military bases in the region.

* Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara (OEF-TS): U.S. forces deployed in Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad

Chad (; ar, تشاد , ; french: Tchad, ), officially the Republic of Chad, '; ) is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic ...

, Mali, Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Tunisia.

**In 2013, the U.S. began providing transport aircraft to the French Armed Forces

The French Armed Forces (french: Forces armées françaises) encompass the Army, the Navy, the Air and Space Force and the Gendarmerie of the French Republic. The President of France heads the armed forces as Chief of the Armed Forces.

Franc ...

during the Mali War.

**President Barack Obama deployed up to 300 U.S. troops to Cameroon in October 2015 to conduct intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance operations against the Boko Haram

Boko Haram, officially known as ''Jamā'at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād'' ( ar, جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد, lit=Group of the People of Sunnah for Dawah and Jihad), is an Islamic terrorist organization ...

terrorist group. Contingency Location Garoua

Contingency Location Garoua is a United States Army base in Garoua, Cameroon. Approximately 200 personnel work at the site. The site is located adjacent to Cameroonian Air Force Base 301.

Operations

The base is used to support military operations ...

, a U.S. Army outpost housing around 200 troops and contractors in Garoua, was established by 2017.

**Four U.S. special operations soldiers and five Nigeriens were killed during an Islamic State ambush in Niger in October 2017. There were around 800 U.S. military personnel in Niger at the time, most of whom were working on constructing a secondary drone base for U.S. and French aircraft in Agadez.

* Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines

* Operation Enduring Freedom – Caribbean and Central America Operation Enduring Freedom – Caribbean and Central America (OEF-CCA) is the name of a U.S.-led regional military operation initiated in 2008, under the control of United States Southern Command. It has a focus on counter-terrorism and is part of t ...

(OEF-CCA)

* Operation Enduring Freedom – Kyrgyzstan

* Operation Enduring Freedom – Pankisi Gorge

The War on Terror saw the U.S. military and intelligence community evolve its asymmetric warfare capabilities, seeing the extensive usage of drone strikes and special operations in various foreign countries including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia against suspected terrorist groups and their leadership.

In 2003, the U.S. and a multi-national

In 2003, the U.S. and a multi-national coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

invaded and occupied Iraq to depose President Saddam Hussein, whom the Bush administration accused of having links to al-Qaeda and possessing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) during the Iraq disarmament crisis. No stockpiles of WMDs were discovered besides about 500 degraded and abandoned chemical munitions leftover from the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s, which the Iraq Survey Group

The Iraq Survey Group (ISG) was a fact-finding mission sent by the multinational force in Iraq to find the weapons of mass destruction alleged to be possessed by Iraq that had been the main ostensible reason for the invasion in 2003. Its final re ...

deemed not militarily significant. The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence found no substantial evidence of links between Iraq and al-Qaeda and President Bush later admitted that "much of the intelligence turned out to be wrong". Over 4,400 Americans and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians died during the Iraq War, which officially ended on December 18, 2011.

In the late 2000s, the United States Naval Forces Europe-Africa

United States Naval Forces Europe-Africa (CNE-CNA), is the United States Navy component command of the United States European Command and United States Africa Command. Prior to 2020, CNE-CNA was previously referred to as United States Naval Forces ...

launched the Africa Partnership Station

Africa Partnership Station (or APS) is an international initiative developed by United States Naval Forces Europe-Africa, which works cooperatively with U.S. and international partners to improve maritime safety and security in Africa as part of U ...

to train coastal African nations in maritime security, including enforcing laws in their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones and combating piracy, smuggling, and illegal fishing.

By 2009, the U.S. had used large amounts of aid and provided counterinsurgency training to enhance stability and reduce violence in President Álvaro Uribe's war-ravaged Colombia, in what has been called "the most successful nation-building

Nation-building is constructing or structuring a national identity using the power of the state. Nation-building aims at the unification of the people within the state so that it remains politically stable and viable in the long run. According to ...

exercise by the United States in this century".

The 2011 Arab Spring resulted in uprisings, revolutions, and civil wars across the Arab world, including Libya, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and Yemen. In 2011, the U.S. intervened in the First Libyan Civil War by providing air support to rebel forces. There was also speculation in '' The Washington Post'' that President Barack Obama issued a covert action, discovering in March 2011 that Obama authorized the CIA to carry out a clandestine effort to provide arms and support to the Libyan opposition. Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

was ultimately overthrown and killed. American activities in Libya resulted in the 2012 Benghazi attack

The 2012 Benghazi attack was a coordinated attack against two Federal government of the United States, United States government facilities in Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya, by members of the Islamic militant group Ansar al-Sharia (Libya), Ansar al ...

.

Beginning around 2012, under the aegis of operation Timber Sycamore and other clandestine activities, CIA operatives and U.S. special operations troops trained and armed nearly 10,000 Syrian rebel fighters against Syrian president Bashar al-Assad

Bashar Hafez al-Assad, ', Levantine pronunciation: ; (, born 11 September 1965) is a Syrian politician who is the 19th president of Syria, since 17 July 2000. In addition, he is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian Armed Forces and the ...

at a cost of $1 billion a year until it was phased out in 2017 by the Trump administration.

2013–2014 saw the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/ISIS) terror organization in the Middle East. In June 2014, during

2013–2014 saw the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/ISIS) terror organization in the Middle East. In June 2014, during Operation Inherent Resolve

Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) is the U.S. military's operational name for the International military intervention against IS, including both a campaign in Iraq and a campaign in Syria, with a closely-related campaign in Libya. Throu ...

, the U.S. re-intervened into Iraq and began airstrikes

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offici ...

against ISIL there in response to prior gains by the terrorist group that threatened U.S. assets and Iraqi government forces. This was followed by more airstrikes

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offici ...

on ISIL in Syria in September 2014, where the U.S.-led coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

targeted ISIL positions throughout the war-ravaged nation. Initial airstrikes involved fighters, bombers, and cruise missiles. The coalition maintains a notable ground-presence in Syria today. The U.S. officially re-intervened in Libya in 2015 as part of Inherent Resolve.

In response to the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, the Obama administration established the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), a program dedicated to bolstering American military presence in Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europe. ...

. The EDI has funded Operation Atlantic Resolve

Operation Atlantic Resolve, though not a "named" operation, refers to military activities in response to Russian operations in Ukraine; mainly the War in Donbass. It was funded under the European Deterrence Initiative. In the wake of Russia's 201 ...

, a collective defense effort to enhance NATO's military planning and defense capabilities by maintaining a persistent rotation of American military air, ground and naval presence in the region to deter perceived Russian aggression along NATO's eastern flank. The Enhanced Forward Presence

Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) is a NATO-allied forward-deployed defense and deterrence military force in Central and Northern Europe. This posture in Central Europe through Poland and Northern Europe through Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, is i ...

(EFP) force was established by NATO.

In March 2015, President Obama declared that he had authorized U.S. forces to provide logistical and intelligence support to the Saudis in their military intervention in Yemen

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, establishing a " Joint Planning Cell" with Saudi Arabia. American and British forces participated in the blockade of Yemen.

President Donald Trump was the first U.S. president in decades to not commit the military to new foreign campaigns, instead continuing wars and interventions he inherited from his predecessors, including interventions in Iraq, Syria and Somalia. The Trump administration often used economic pressure against international adversaries such as Venezuela and the Islamic Republic of Iran. In 2019, tensions between the U.S. and Iran triggered a crisis in the Persian Gulf which saw the U.S. bolster its military presence in the region, the creation of the International Maritime Security Construct

The International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC) is a consortium of countries whose official stated aim is the maintenance of order and security in the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, Gulf of Aden and Southern Red Sea, particularly regarding marit ...

to combat attacks on commercial shipping, and the assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

of prominent Iranian general Qasem Soleimani.

In March 2021, the Biden administration designated al-Shabaab in Mozambique as a terrorist organization and, at the request of the Mozambique government, intervened in the Cabo Delgado conflict. Army Special Forces were deployed in the country to train Mozambican marines.

See also

* American imperialism * American exceptionalism * Territorial evolution of the United States * United States and state terrorism * Criticism of United States foreign policy * List of United States drone bases * List of armed conflicts involving the United States * List of the lengths of United States participation in wars * Military history of the United States * Historic regions of the United States * Neoconservatism *Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

* Foreign interventions by the Soviet Union

* Foreign interventions by China

* Foreign interventions by Cuba

* Foreign electoral intervention

Foreign electoral interventions are attempts by governments, covertly or overtly, to influence elections in another country.

Academic studies Intervention measurements

Theoretical and empirical research on the effect of foreign electoral inte ...

* New Imperialism

References

{{American conflicts History of the foreign relations of the United States History of United States expansionism United States American Empire